Whose Words Are These? Authorship in the Age of AI

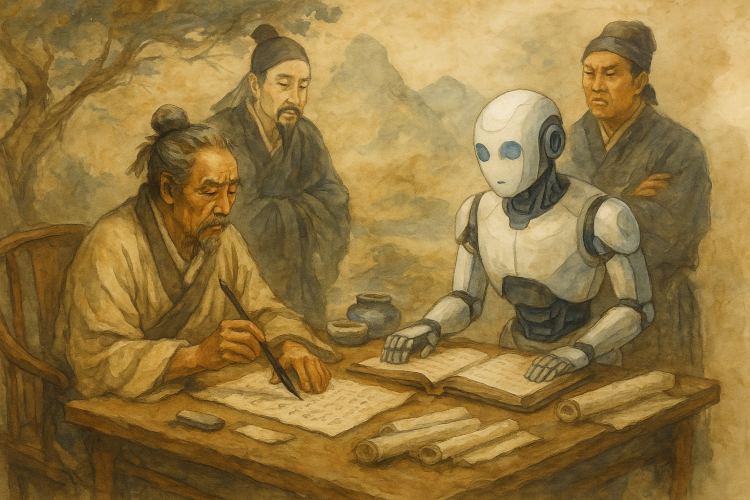

Is using AI to write really “cheating”? This essay challenges that claim by comparing AI writing to ghostwriting and editorial overreach. In doing so, it redefines authorship for the modern era and argues that intent—not tools—determines the true soul of a writer's work.

In an era where artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok are becoming as common as word processors once were, a curious accusation has emerged in literary circles: that using AI constitutes "cheating." Critics argue that AI-assisted writing is somehow less authentic, less intellectual, and even less ethical than traditionally authored work. But a closer look reveals that this claim lacks historical depth, moral consistency, and conceptual clarity.

To label AI-assisted writing as “cheating” is to conflate the use of tools with the abandonment of thought. Writing—regardless of the medium—requires cognition, intention, and judgment. When a writer uses AI thoughtfully, they are still making choices, exercising discernment, and shaping meaning. The process may be enhanced by technology, but the thinking remains human. If the question is whether the writer is thinking, then the answer is evident in the clarity, coherence, and argumentative power of their prose.

If using AI is cheating, what then are we to make of the long-standing and widespread practice of ghostwriting? Consider the numerous bestselling authors and public figures whose names adorn covers they did not personally write. James Patterson, one of the most prolific authors alive, employs a stable of co-writers and ghostwriters to help turn his outlines into full novels. V.C. Andrews’ name continues to publish new titles decades after her death, thanks to ghostwriter Andrew Neiderman. Celebrities from Donald Trump to Beyoncé rely on ghostwriters to shape their public narratives. In these cases, the public is often unaware—or chooses to overlook—the extent of outside involvement. Yet these works are celebrated, marketed, and financially rewarded. The ethical discomfort surrounding ghostwriting rarely receives the same moral outrage as AI usage, even though the ghostwriter may perform most of the intellectual and creative labor. By contrast, an AI-assisted writer typically remains the architect of the thought, tone, and message.

This suggests that the “cheating” accusation is not truly about preserving intellectual authenticity, but about maintaining a status quo where only certain tools—and certain people—are allowed to shape literature. Critics often fear that AI enables a new era of intellectual dishonesty. But cheating did not begin with AI—it is a human behavior rooted in intent, not in technology. Long before neural networks, people plagiarized essays, hired ghostwriters, and took credit for others’ labor. AI has not created dishonesty; it has merely become a new symbol onto which old fears are projected.

As one critique aptly put it: “Cheating is an attitude disease created by the failing social system governed by human management anatomy.” In other words, cheating arises when systems reward results over integrity, competition over learning, and image over substance. In such environments, the incentive to deceive exists with or without AI. The root problem is cultural, not computational.

If AI-assisted writing draws criticism for altering authorial voice or obscuring authorship, then we must also question the influence of editors—particularly in the traditional publishing world. Many iconic works have been significantly reshaped by editorial intervention, sometimes to the point of near co-authorship. Raymond Carver's minimalist style, for example, is often attributed more to his editor, Gordon Lish, than to Carver himself. Lish cut, rewrote, and reshaped Carver’s stories so dramatically that the final published versions were starkly different from the originals. Carver himself expressed regret, feeling his more humane and emotionally complex voice had been lost.

Similarly, To Kill a Mockingbird was born from a vastly different manuscript titled Go Set a Watchman. Harper Lee’s editor, Tay Hohoff, guided the transformation, helping Lee rewrite characters, change the structure, and shift the central themes. The published novel bears little resemblance to the original draft. Even titans like Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, and William Faulkner were deeply shaped by editors who cut, rearranged, or heavily polished their prose. In each case, the final product—celebrated as the author’s vision—was, in part, the creation of another hand. Where, then, do we draw the line? If a developmental editor can rewrite entire chapters without public acknowledgment, why is a writer using AI to brainstorm or rephrase a paragraph seen as dishonest?

The key difference may lie in visibility. Ghostwriting and editorial overreach are often invisible to readers. Their invisibility makes them acceptable by default. In contrast, AI use is new, visible, and misunderstood. Its transparency becomes its liability—but also its strength. When a writer uses AI as a creative partner—generating ideas, experimenting with tone, improving structure—they retain full editorial control. The writer can accept, reject, or modify every suggestion. This interaction is arguably more honest than a ghostwritten book or a manuscript rewritten by an unseen editor. In AI-assisted writing, the thought remains with the author, while the machine serves as a catalyst, not a substitute.

The moral panic over AI-assisted writing is not about writing—it’s about change. It’s about fear that long-standing hierarchies of gatekeeping, mentorship, and access are being destabilized. For many, AI represents the democratization of a craft previously preserved for those with time, training, or insider connections. But just as typewriters didn’t kill poetry and spell-check didn’t destroy prose, AI will not make thinking obsolete. In fact, when used thoughtfully, it can sharpen thinking, expose inconsistencies, and expand creative possibility. The question we should be asking is not “Did you use AI?” but “Did you think? Did you write with intention? Did you create something meaningful?”

As we redefine what it means to write in the age of machines, we must do so with historical awareness and ethical consistency. Accusations of cheating must be based on intent, not tools. Authenticity is not determined by whether a writer used AI, an editor, or a ghostwriter—it’s determined by whether the work is the honest product of their thinking and creative spirit. In the end, literature has always been collaborative. Every sentence is shaped by the language we inherit, the tools we use, and the people—visible or invisible—who help refine our thoughts. Artificial intelligence is just the newest participant in this ongoing conversation. And unlike ghostwriters or editors who may rewrite without trace, AI places the writer firmly in the driver’s seat.