The Unlit Self

In a world fixated on visibility, this lyrical essay explores the quiet defiance of writing for oneself. Through Kafka, Woolf, Plath, and Sartre, it becomes a meditation on authorship as self-inquiry—a tender rebellion against judgment and a journey into the unlit self.

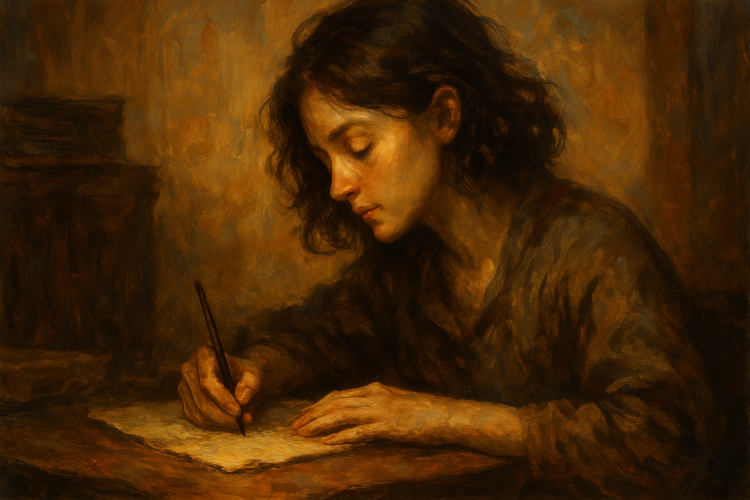

In a world that often prioritizes external validation, the act of writing can be a profound exercise in introspection. But what happens when the writer turns the lens inward, crafting stories not for an audience’s approval, but for themselves? What if the true purpose of writing isn’t to convey meaning to others, but to navigate the labyrinth of one’s own mind? In these moments of deep self-reflection, the author’s voice emerges not as a performer for the audience, but as an honest, vulnerable presence—stripped of the armor of expectation and judgment.

At the heart of this introspective writing lies a desire to explore the most private parts of the self, untouched by the scrutiny of the world. The act of writing becomes a means of self-understanding rather than external communication. It’s about peeling back layers of identity, acknowledging one’s fears, desires, and doubts. It’s a kind of quiet defiance against a world that constantly judges us based on external standards—a space where the writer is free to be themselves without fearing judgment.

Some of the greatest literary works emerge from this introspective void. Franz Kafka’s The Trial and The Metamorphosis are prime examples. Kafka, trapped in his own world of alienation and anxiety, created narratives that reflect his deepest fears of incomprehensible authority and the absurdity of existence. His characters—especially Gregor Samsa—become extensions of his own internal struggles. These works were not created with an audience in mind, but rather as a private confrontation with Kafka’s own sense of isolation, guilt, and futility. Readers are invited into his world, but ultimately, Kafka’s writing serves to uncover his inner turmoil.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse take a similar approach, with characters who are not simply moving through time but reflecting on it, reflecting on themselves. Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness writing offers us a window into the minds of her characters, exploring their thoughts in intimate detail. Woolf’s method was not about telling a story in the conventional sense, but rather about mapping the ever-shifting landscape of the human mind. Her novels feel less like a narrative and more like a meditation on time, identity, and existence—a personal inquiry that is not meant to be “solved,” but felt.

The question of judgment plays a central role in the need for this kind of writing. Why do we feel the constant need to illuminate ourselves, to shine a light on our every thought and action? Perhaps it’s because we fear judgment—fear the scrutiny of others, especially those in power or society’s elite. We shine light on parts of ourselves that might otherwise remain hidden, thinking that in doing so, we can protect ourselves from being misunderstood or rejected. This desire for visibility is often a mask we wear, believing that by exposing every aspect of our lives, we can make ourselves more palatable or acceptable.

But this process often leaves us disconnected from our true selves. The constant search for external validation can make us forget that our value doesn’t lie in the approval of others, but in the acceptance of who we are—flaws and all. And so, we lose touch with the quiet, unlit parts of ourselves that don’t require the glaring spotlight of judgment. These parts are the raw, unfiltered pieces of our existence that make us who we truly are.

The idea of judgment is not just a matter of others’ perceptions—it is deeply intertwined with the judgment we place on ourselves. In trying to meet external standards, we inevitably impose them upon our own sense of self. We begin to write to please, not to explore. We begin to live in a world where every action is measured against some invisible yardstick of worth, and we lose sight of the simple truth: we are enough as we are, in all our complexity.

There’s a quiet resistance in writing that doesn’t demand approval. It’s the resistance of authors like Jean-Paul Sartre, whose Nausea confronts the absurdity of existence and the feeling of alienation. Sartre’s protagonist, Roquentin, is not just navigating a plot—he is navigating his own understanding of life, grappling with the discomfort of realizing that existence itself is without inherent meaning. Sartre’s narrative is deeply personal, offering no clear answers but instead inviting readers into the disorienting, sometimes terrifying world of introspection.

Similarly, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar is less a novel than a dissection of the self. Plath’s writing is a window into the mind of her protagonist, Esther Greenwood, as she struggles with identity, mental illness, and societal expectations. Through Esther’s journey, Plath captures the dissonance between the person we are and the person we are told to be, making it clear that the struggle is not just external, but internal—a battle for self-acceptance in a world that demands conformity.

In these works, the writing serves not to entertain or inform, but to feel. They are maps of the mind, written not for the world, but for the writer’s own understanding of their place within it. The most profound works of literature often stem from this place of self-exploration—a place where the writer is not merely an artist crafting a product, but a person seeking to understand their own existence.

What, then, can we learn from these deeply personal works? Perhaps that true connection lies not in being understood by others, but in understanding ourselves. And in that understanding, we find that we are not alone in our struggle, in our search for meaning. We are, in fact, connected by our shared humanity, by the simple fact that we are all navigating the same world, often in silence, often without answers.

The lesson is this: the most powerful form of writing is the one that begins with the self, not for the purpose of showing the world, but for the purpose of discovering who we are. And in that discovery, we find the universal threads that connect us all.