Glass Worlds and Quiet Witnesses

In a room shared by silence and stillness, a betta fish becomes more than a quiet companion—it becomes a mirror. This lyrical essay explores the gentle, grounding presence of animals in a writer’s world, offering a meditation on rhythm, solitude, and the poetry of being.

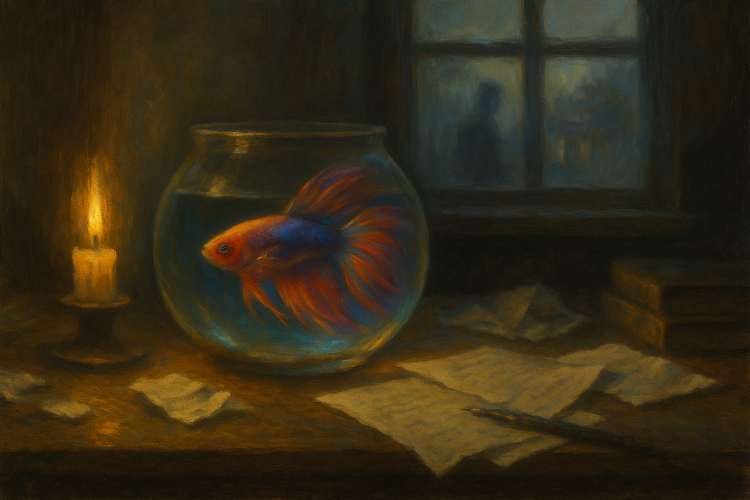

There’s a betta fish beside my desk. It swims in silence, through an environment that is wholly its own. Not quite blue — something closer to ember, ink, or dusk depending on the hour. It lives in stillness, untroubled by time, undisturbed by the sounds that buzz just outside the glass. While I write, it moves. While I pause, it hovers. We are both here — separately, together — inhabiting different worlds stitched by one moment of presence.

Writers have always surrounded themselves with pets. In the lore of literary lives, pets are almost mythic: Ernest Hemingway’s six-toed cats, Virginia Woolf’s spaniels, Haruki Murakami’s nameless cats that walk in and out of his stories. Neil Gaiman’s dog often appears beside his desk in interviews. These animals aren’t merely companions — they’re part of the writer’s space, ritual, and even voice. They offer something the literary process itself demands: presence, patience, and an unwavering ability to simply be.

And maybe that’s the secret. Writing is a lonely art, even when it’s joyful. It asks you to sit inside your own mind long enough to make sense of it. In that space, pets become a kind of anchor — tethering the writer to something real and tender. A heartbeat in the room. A witness to the page.

In the past, these companions often found their way into the work itself. Hemingway’s cats appear in anecdotes and margins; Woolf’s spaniels show up in letters and essays. These animals blurred the line between life and literature. They lived in the writer’s small, private world — a world where ideas are fragile and solitude is sacred — and became part of the language built there.

But in today’s literary world, this intimacy between writer and pet seems less visible. Perhaps it's cultural shift — the modern writer is less likely to mythologize their surroundings, more private, more curated. Perhaps it’s the era of distraction: algorithms, deadlines, and the performative demands of being an “online author” leave little room for the quiet domestic rituals that once defined writing life. Or maybe we still have those relationships — we just don’t speak of them as much.

Which brings me back to the fish beside my desk.

Betta fish don’t fit the usual pet-writer mold. They don’t curl up in your lap. They don’t nudge your hand or demand affection. They’re not companions in the traditional sense. They exist — silent, self-contained, and strangely regal — within a world as surreal as it is serene. And yet, in that silence, there’s something unmistakably profound.

Each morning, I feed my fish. I watch it rise to the surface and flick its tail in that graceful, effortless way only a fish can. Then it drifts back into its realm — a miniature universe of floating plants, slow ripples, and drifting shadows. I return to my keyboard. We go about our day — both suspended in glass worlds. Mine digital, full of thoughts; theirs liquid, full of light and motion.

There’s no noise between us. No exchange. And yet, this gentle ritual — of observing, of caring, of simply being in each other’s presence — brings peace. In a world that demands productivity, response, and constant attention, a fish teaches a different rhythm. One where silence is not a lack, but a space. A place to reflect. A place to write.

I didn’t expect this when I brought the fish home. At first, it was a small gesture — something quiet and low-maintenance to accompany the hours I spend writing. But over time, I began to notice the ways its presence shaped the room. Its movements became punctuation in my day. Its stillness became my own. When the words feel jagged, or the page feels far away, I often look over and find the fish just floating — suspended in the middle of its world, unbothered by momentum. And strangely, it helps.

Perhaps pets — of any kind — aren’t just part of the writer’s world. Perhaps they offer an alternate one. A reality where time moves differently. Where being matters more than doing. Where survival is an art form in itself.

The betta fish, in particular, feels symbolic. Solitary by nature, vibrant yet delicate, often misunderstood. It mirrors something many writers know intimately — the paradox of being alone yet deeply observant, silent yet expressive, isolated yet full of vivid inner color. Its life unfolds behind glass, but its beauty is undeniable. Much like the work we create, often unseen, yet deeply alive.

Not every writer needs a muse that purrs or barks. Some of us find companionship in creatures that ask for nothing and teach us everything. In the subtle choreography of a betta’s movement, I’ve learned something essential about my own rhythms. That not all progress is loud. That silence can be full. That creativity is not a chase — it’s a drift, a watch, a gentle submersion into stillness.

I write beside a tank now. Not always, not every day, but often enough that I’ve started to feel its absence when I’m away. And maybe, just maybe, this is what writers have always sought in their pets — not inspiration in the traditional sense, but presence. A reminder of life lived just outside the text. A tether to something calm and breathing, something that asks for care without words.

In an age of noise, I find meaning in that quiet. I find peace in the world of the fish, even as I write in my own. And in the space between us — clear, flickering, shared — something like poetry blooms.